Events

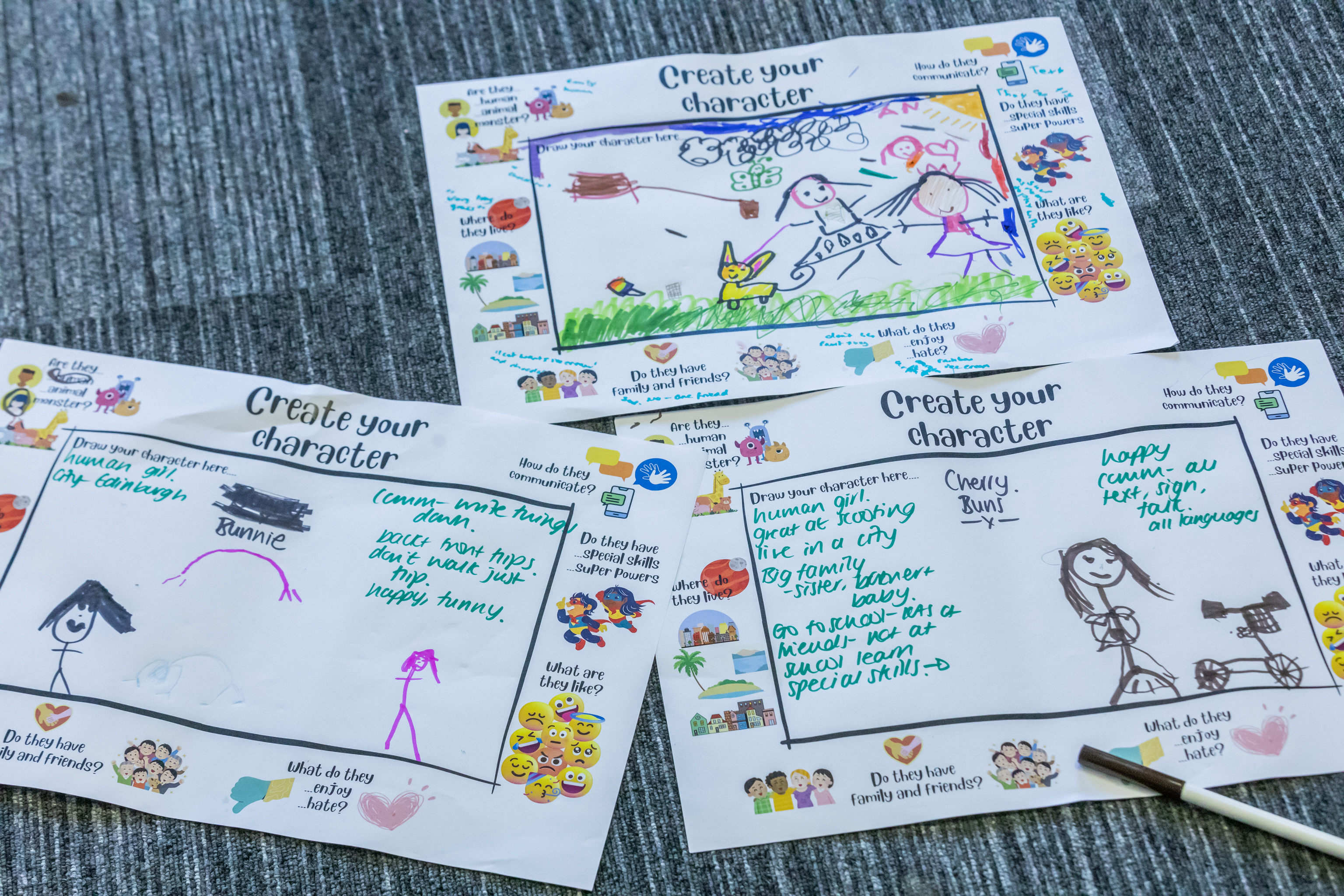

This rescheduled event took place on 4th January at Deaf Action. This was meant to take place during Scottish Book Week but was rescheduled due to a winter storm. It was great fun to host this storytelling event. Luigi Lerose was an excellent facilitator, starting by telling the traditional story of Little Red Riding Hood and then retelling it with Little Red being deaf. The children then made whimsical and imaginative characters that were deaf with a variety of ways to communicate, one was a back flip expert and another could fly. Luigi expertly weaved the children’s characters, Bunny, Cherry and Emily into a fun and sweet story that the children co-created. The children and parents all enjoyed the afternoon and the story! It was a privilege to deliver this event and a huge thank you to Deaf Action, the Scottish Book Trust, Heriot Watt University, Luigi Lerose, Emmy Kauling and to all the families who attended.

Conferences

International Research Society for Children’s Literature Conference, Salamanca University, Salamanca: June 2025

Presentation Abstract:

Picture books as Borderlands: Betwixt and between deaf and hearing worlds

Approximately 90% of deaf children are born into hearing families (National Deaf Children’s Society, 2016). As a result they may not automatically be exposed to a natural visual language such as British Sign Language (BSL), have deaf signing role models, friends or be engaged with the deaf signing community and culture. This paper will explore how picture books that contain deaf representation and include BSL in the text and illustrations, can create liminal spaces for parents and children to develop communication skills including translanguaging practices, explore deaf identities and deaf ways of being. For the parents these books can also open up the concept of Deaf child futures, the options and potential that they envision for their child (Russell, 2023).

Deaf representation in British picture books, while limited, offers children and their parents a window into the deaf signing experience, which for many hearing parents is an entirely new cultural experience. Picture books have the potential to act as a gateway into the borderland of the deaf signing world, introducing BSL, and deaf culture to parents which could act as a bridge into real world experiences (Golos and Moses, 2011).

This paper will cover the findings of my PhD research into deaf representation in picture books, and how families can develop their understanding of the deaf experience through co-reading with their child. The paper will summarise the findings from the analysis of a corpus of British picture books featuring deaf characters and from interviews with hearing parents of deaf children on their experience and interpretations of these narratives.

References

Golos, D.B. and Moses, A.M. (2011) ‘Representations of deaf characters in children’s picture books’, American Annals of the Deaf, 156(3), pp. 270-282.

National Deaf Children’s Society (2016) Right from the start: A campaign to improve early years support for deaf children. London. Available at: https://www.ndcs.org.uk/media/1283/right_from_the_start_campaign_report_final.pdf (Accessed: 25/04/2023).

Russell, E.J. (2023) “We don’t know what we don’t know”. How do hearing parents understand good outcomes for their deaf children? A hearing parent’s perspective. University of Manchester.

Children’s Literature and Translation Studies Conference

Stockholm University, Stockholm: August 2024

Presentation Abstract

Storybooks and translanguaging: From the classroom to the family

The majority of deaf children are born into hearing families; as a result, they may not automatically be exposed to a natural visual language such as British Sign Language (BSL) from birth. This paper will explore how hearing parents of deaf children use multimodal picture books to develop their own translanguaging approaches within the family setting. Translanguaging describes the linguistic repertoire of a person: for deaf people and those hard of hearing translanguaging has, whether positively or negatively, been integrated into everyday communicative life to create meaning (De Meulder et al., 2019).

Research into the use of multilingual picture books in English and Spanish has shown the positive impact translanguaging approaches have on language and literacy development. These include the multimodal use of reading, speech, movement, text, and illustrations to repeat and practice languages which can enhance a child’s linguistic repertoire. Tentative research into translanguaging approaches in BSL and English in the classroom have demonstrated the potential of adopting translanguaging methods to develop language and literacy skills (Swanwick, Wright and Salter, 2016). The key difference between these approaches is that within the Spanish-English dyad parents often have one language as a heritage language while the other is the dominant language of the country of residence. For deaf-hearing families, hearing parents are new learners of sign language and therefore can lack the skills and confidence in teaching and sharing the language with their child.

Deaf children of hearing parents are at risk of language deprivation which has significant consequences across various domains such as cognitive and emotional development (Caselli, Pyers and Lieberman, 2021). Parent and child co-reading of picture books offers a natural way to support the parent child attachment relationship, alongside developing communication and language skills. However, translanguaging has yet to be explored as a way of understanding deaf hearing family dynamics, especially when it comes to understanding how hearing parents of deaf children can use a translanguaging approach to help them begin to navigate and migrate towards Deaf communities and culture.

I will report on the preliminary results of an online survey exploring hearing parents’ shared reading experiences with their deaf child and their use of translanguaging approaches within the home. I will then present a multimodal analysis of example picture books such as “What the Jackdaw Saw” by Julia Donaldson, exploring how these picture books, which incorporate BSL within the text and illustrations, could be used to develop translanguaging as a tool to develop a family’s linguistic repertoire.

References

Caselli, N., Pyers, J. and Lieberman, A.M. (2021) ‘Deaf children of hearing parents have age-level vocabulary growth when exposed to American Sign Language by 6 months of age’, The Journal of Pediatrics, 232, pp. 229-236. Available at: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.01.029

De Meulder, M., Kusters, A., Moriarty, E. and Murray, J.J. (2019) ‘Describe, don’t prescribe. The practice and politics of translanguaging in the context of deaf signers’.

Swanwick, R., Wright, S. and Salter, J. (2016) ‘Investigating deaf children’s plural and diverse use of sign and spoken languages in a super diverse context’, Applied Linguistics Review, 7(2), pp. 117-147.

Kid Crip Lit Conference

Cambridge University, Cambridge: April 2024

Presentation Abstract

Hands and Hearts: Deafness and Sign Language in Children’s Picture Books

This paper aims to discuss and explore the representation of deafness and sign language within children’s picture books. Exploring how representation has developed over the last decade and the intersection of deaf studies, disability, language use, multimodality and narrative.

Since Saunders (2004) article, children’s literature has made strides with greater diversity, representation and narratives that challenge ableist views (Hayden and Prince, 2023). However, this is not necessarily true for deaf children who rarely see themselves represented within children’s picture books, when they do, they are often presented as disabled or medicalised rather than as part of a cultural and linguistic minority (Golos, Moses and Wolbers, 2012). While many in the deaf community would advocate that they are not disabled, the issues around representation in, and accessibility of children’s literature intersects deafness and disability studies.

In Henner and Robinson (2021) article on cripping linguistics they argue that signed languages are considered unnatural and atypical. Within children’s literature there are limited examples of signed languages being incorporated or translations being provided with the text. The limited availability of children’s books containing or translated into sign language potentially offers further evidence of the devaluation of sign languages as deviant or disordered. This paper will explore the representation of deaf characters and how their identity, communication, cultural and linguistic choices are portrayed.

Children’s literature is often seen as a tool used by parents to support the educational, social and emotional development of their children. Narratives help children understand society, culture, social norms and values (Stephens, 1992; Saunders, 2004). Within the genre of picture books children can begin to understand their own place and value within society. Given that there is a limited selection of children’s picture books containing deaf characters and themes, what are the narratives, values and access to language being offered to deafhearing families?

References

Golos, D.B., Moses, A.M. and Wolbers, K.A. (2012) ‘Culture or disability? Examining deaf characters in children’s book illustrations’, Early Childhood Education Journal, 40(4), pp. 239-249. Available at: 10.1007/s10643-012-0506-0

Hayden, H.E. and Prince, A.M. (2023) ‘Disrupting ableism: Strengths-based representations of disability in children’s picture books’, Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 23(2), pp. 236-261.

Henner, J. and Robinson, O. (2021) ‘Unsettling languages, unruly bodyminds: Imaging a crip linguistics’.

Saunders, K. (2004) ‘What disability studies can do for children’s literature’, Disability Studies Quarterly, 24(1).

Stephens, J. (1992) Language and ideology in children’s fiction. New York, USA Longman.

Encounters Conference

University of Glasgow, Glasgow: June 2023

Presentation Abstract

What can hearing parents learn about the Deaf World through the looking glass?

The majority of deaf children (90-95%) are born to hearing parents, for many of these parents their child is the first deaf person they have met (National Deaf Children’s Society, 2016). Becoming a parent and then discovering that your child has an unknown and unexpected difference to you can be overwhelming (Young, 2018). This work in progress will explore some of the challenges and opportunities available to hearing parents, and how children’s literature can be used to help families begin to explore this new world of deafness, culture, storytelling and sign languages.

The d/Deaf community are a minority and experience inequalities and discrimination (Bauman, 2008). Parents play a significant role in shaping how their child develops their identity, self-esteem and ways to challenge these inequalities when they occur. Can parental socialisation be supported through children’s stories as a way to explore these issues? Stories are our way of understanding experience, sharing, learning and healing (Etherington, 2020). Narratives help us understand the world around us and children’s stories are where we all begin. This presentation aims to explore the current research on these topics as a work in progress of the larger PhD research project.

References

Bauman, H.-D.L. (2008) Open your eyes Deaf studies talking. Edited by Bauman, H. D. L. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Etherington, K. (2020) ‘Becoming a narrative inquirer’, in Bager-Charleson, S. and Mcbeath, A. (eds.) Enjoying research in counselling and psychotherapy: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods research. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 71-93.

National Deaf Children’s Society (2016) Right from the start: A campaign to improve early years support for deaf children. London. Available at: https://www.ndcs.org.uk/media/1283/right_from_the_start_campaign_report_final.pdf (Accessed: 25/04/2023).

Young, A. (2018) ‘Deaf children and their families: Sustainability, sign language, and equality’, American Annals of the Deaf, 163(1), pp. 61-69. Available at: 10.1353/aad.2018.0011